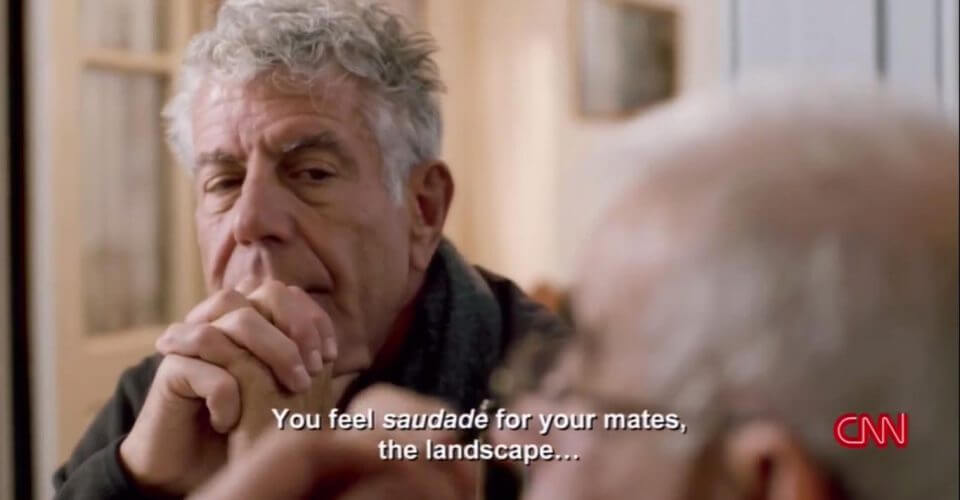

Saudade. The Portuguese word that allegedly defies direct translation. Anthony Bourdain described it as “…a kind of melancholy – a yearning to get back to something or someone lost, perhaps to a happier time.” Close, but not quite! Maybe only a Portuguese can try to describe it. But, truth be told, Tony, we miss you deeply — and that, too, is Saudade.

This, too, is Saudade!

Every Portuguese person has a deep connection to their roots. In fact, if a Portuguese person had roots like a tree, they would be like the oak tree — sturdy and strong enough to grow between huge rocks. When we’re talking about the people of the North of Portugal, their roots would go through granite, entwining and becoming part of it.

When you walk around Porto or Lisbon, it’s common to hear locals using the word Aldeia (village) to refer to their family’s hometown. It is a fact that, by the late 19th century, thanks to industrialization, many families moved from the countryside to the big cities. They were seeking better opportunities — chasing a kind of Portuguese version of the American Dream.

The expression “Vou à Aldeia” (I’m going to my village), although it might sound as though city dwellers have a higher status, actually conveys a connection to the Portuguese untranslatable word. Saudade.

More than a return to the past, this word expresses a wishful longing for a better future. You visit the aldeia and dream of retirement, imagining the day you can reclaim your rightful place and restore what was taken — returning the tree to its roots. You make peace with your homeland and dedicate your last good years to caring for it.

Saudade is also tied to food

Saudade is a kind of Happy Place where you go to reconnect with your DNA. It reminds us of what truly matters and shapes who we are. Using Saudade as a spiritual time machine to revisit our loved ones is one way to re-cherish the things and feelings that made them special. This isn’t always painless. It’s a pleasant pain, tied to something you’ll never have again but which profoundly shaped your core, helping build the best parts of your character.

People also connect saudade to food — not the food itself, but the emotions it evokes. The memory of a meal is inseparable from the people who surrounded you during that epic meal.

Take Christmas Eve dinner in Portugal: the food itself — boiled salted cod, boiled potatoes, and three types of kale — is modest, even boring. But sharing it with family transforms it into something magical, making it a conduit for reconnecting with those good feelings whenever you repeat the meal on other occasions.

Mom’s cooking feels special because it holds the emotional connection of the umbilical cord — a direct link to the feelings that tie you to family. This, too, is Saudade!

Saudade is being happy and sad at the same time

Saudade is a walk down memory lane, but it’s a two-way street. You should go back, gather the good moments, and then return to the present. If you stay too long, it becomes a one-way ticket to depression.

Scientifically one can relate Saudade with Marcel Proust’s “Involuntary Memory”. Proust defines it as:

- A moment when everything suddenly comes to mind;

- A whirlwind of situations and feelings connected to a past that will never return;

- A situation that does not repeat itself that brings us back to an ideal moment in Time and Space;

- Not an actual Memory, because most of it is actually fabricated, but an involuntary combination of factors that give us good feelings.

Saudade is a “black box” of all the good moments that have influenced us and made us who we are today. Revisiting it isn’t a Freudian exercise in self-analysis; it’s a direct route to the happy place that can comfort us and, if only momentarily, lift us from misery.

The nation’s Saudade

Portugal possesses this unique word due to its particular historical circumstances. And it’s a shared feeling throughout the country, despite the differences between North and South, inland and coastal areas.

The nation’s Saudade, so present in Portuguese literature, often refers to golden moments in Portugal’s history. People often link its birth to the disappearance of King Sebastian (D. Sebastião), but it has older roots, like the Portuguese Cantigas de Amor (11th-century love songs). These songs, while expressing longing for a beloved woman, always carried a sad connotation, even as they celebrated happy moments with her. Nostalgia, for something good yet irretrievably gone, is at the heart of Saudade.

Moments of glory, such as:

- The definition of Portugal’s borders in 1267;

- The avoidance of annexation by Spain in 1383-85;

- Tthe Age of Discoveries;

- The Restoration of Independence in 1640.

… These are all ingrained in the nation’s collective memory — amplified by the Estado Novo dictatorship’s propaganda machine (Portuguese Dictatorship period) that tireless used all these moments to exacerbate the nationalist spirit.

This is Portuguese Saudade: the memory of a small, resource-limited nation that achieved extraordinary feats, “giving new worlds to the world.”

This return to that Happy Place should be the example that Portuguese should use to define its character as a Nation but it’s not observed the same way throughout the country.

Saudade in Porto

In Porto, for instance, we take more advantage of Saudade because, in times of crisis, Porto is always the first to reap the fruits of looking to the past.

Maybe our involuntary memory has more willpower than the rest of the country; or perhaps it’s because our happy place feels closer in time: the implantation of liberalism, the cultural and political revolutions of the 19th and 20th centuries, the historical resistance to central government control, and our enduring thirst for culture. These make us use Saudade as fuel for a brighter future.

When Anthony Bourdain was shooting in Porto for his show, Parts Unknown (Season 9, Episode 10), I was fortunate to discuss Saudade with him and Pedro Caxote, the fisherman who cooked an amazing lamprey eel for us. Tony initially framed Saudade as a mix of nostalgia and sadness. I had to tell him he was wrong, and while he thought I was bold to contradict him on CNN, Senhor Pedro came to my aid and talked about Saudade in its own words.

Pedro shared his experience in the Portuguese Colonial War, which sent a generation overseas between 1961 and 1974. Tears came to his eyes when he was speaking about the camaraderie, the smells, the landscape, and the feelings that shaped him — even though he served in one of the war’s worst locations, Guinea. Amid the horrors, Pedro still finds good memories to cherish, bringing himself to happy tears before returning to the present, restored.

It’s not just about longing for what’s gone

Bourdain understood this in part, but not fully. Saudade isn’t sadness — it’s the fuel that keeps us going. It’s the tears you shed for what you loved, the laughter you find in the remembering, and the drive to take those memories forward into something new. If you let it, Saudade is a guide. It’s not just about longing for what’s gone — it’s about carrying the best of it forward.

Ricardo Brochado, founder of City Tailors, beautifully captures saudade in this blog post, now featured on the Taste Porto blog as part of the fusion between City Tailors and Taste Porto.